Most damage caused by badgers results from their digging in pursuit of prey. Open burrows create a hazard to livestock and horseback riders. Badger diggings in crop fields may slow harvesting or cause damage to machinery. Digging can also damage earthen dams or dikes and irrigation canals, resulting in flooding and the loss of irrigation water. Diggings on the shoulders of roads can lead to erosion and the collapse of road surfaces. In late summer and fall, watch for signs of digging that indicate that young badgers have moved into the area. Continue reading Identifying Badger Damage

Month: May 2007

Badger Habitat and Food Habits

Badgers prefer open country with light to moderate cover, such as pastures and rangelands inhabited by burrowing rodents. They are seldom found in areas that have many trees.

Badgers are opportunists, preying on ground-nesting birds and their eggs, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Common dietary items are ground squirrels, pocket gophers, prairie dogs, and other smaller rodents. Occasionally they eat vegetable matter. Metabolism studies indicate that an average badger must eat about two ground squirrels or pocket gophers daily to maintain its weight. Badgers may occasionally kill small lambs and young domestic turkeys, parts of which they often will bury.

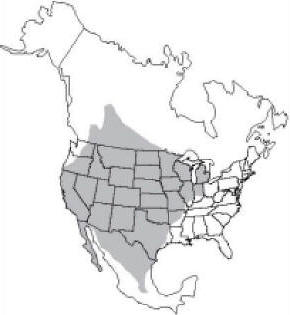

Badger Range in the United States

The badger is widely distributed in the contiguous United States. Its range extends southward from the Great Lakes states to the Ohio Valley and westward through the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast, though not west of the Cascade mountain range in the Northwest (Fig. 2). Badgers are found at elevations of up to 12,000 feet (3,600 m).

Badger Identification

The badger (Taxidea taxus) is a stocky, medium-sized mammal with a broad head, a short, thick neck, short legs, and a short, bushy tail. Its front legs are stout and muscular, and its front claws are long. It is silver-gray, has long guard hairs, a black patch on each cheek, black feet, and a characteristic white stripe extending from its nose over the top of its head. The length of this stripe down the back varies. Badgers may weigh up to 30 pounds (13.5 kg), but average about 19 pounds (8.6 kg) for males and 14 pounds (6.3 kg) for females. Eyeshine at night is green.

Avoiding Human-Bear Conflicts

Preventing Bear Attacks. Black and grizzly bears must be respected. They have great strength and agility, and will defend themselves, their young, and their territories if they feel threatened. Learn to recognize the differences between black and brown bears. Knowledge and alertness can help avoid encounters with bears that could be hazardous. They are unpredictable and can inflict serious injury. NEVER feed or approach a bear. Continue reading Avoiding Human-Bear Conflicts

Shooting to Control Black Bear

Shooting is effective, but often a last resort, in dealing with a problem black bear. Permits are required in most states and provinces to shoot a bear out of season. To increase the probability of removing the problem bear, shooting should be done at the site where damage has occurred. Bears are most easily attracted to baits from dusk to dark. Place baits in the damaged area where there are safe shooting conditions and clear visibility. Use large, well-anchored carcass baits or heavy containers filled with rancid meat scraps, fat drippings, and rotten fruit or vegetables. Establish a stand roughly 100 yards (100 m) downwind from the bait and wait for the bear to appear. Strive for a quick kill, using a rifle of .30 caliber or larger. The animal must be turned over to wildlife authorities in most states and provinces.

Calling bears with a predator call has been reported to offer limited success. If nothing else works, it can be tried. It is best to use two people when calling since the bear may come up in an ugly mood, out of sight of the caller. As with any method of bear control, be cautious and use an adequate-caliber rifle to kill the bear. Call in the vicinity of the damage, taking proper precautions by wearing camouflage clothing, orienting the wind to blow the human scent away from the direction of the bear’s approach, and selecting an area that provides clear visibility for shooting. See Blair (1981) for bear-calling methods. Some states allow the use of dogs to hunt bears. Guides and professional hunters with bear dogs can be called for help. Place the dogs on the track of the problem bear. Often the dogs will be able to track and tree the bear, allowing it to be killed, and thus solving the bear problem quickly.

Trapping Black Bear

Culvert and Barrel Traps. Live trapping black bears in culvert or barrel traps is highly effective and convenient (Fig. 6). Set one or two culvert traps in the area where the bear is causing a problem. Post warning signs on and in the vicinity of the trap. Use baits to lure the bear into the trap. Successful baits include decaying fish, beaver carcasses, livestock offal, fruit, candy, molasses, and honey. When the trap door falls, the bear is safely held without a need for dangerous handling or transfer. Bears can be immobilized, released at another site, or destroyed if necessary. Trapped bears that are released should first be transported at least 50 miles (80 km), preferably across a substantial geographic barrier such as a large river, swamp, or mountain range, and released in a remote area. Remote release mechanisms are highly recommended. Occasionally, food-conditioned bears will repeat their offenses. A problem bear should be released only once. If it causes subsequent problems it should be destroyed.

Foot Snares. The Aldrich-type foot snare (Fig. 7) is used extensively by USDA-APHIS-ADC and state wildlife agency personnel to catch problem bears. This method is safe, when correctly used, and allows for the release of nontarget animals. Bears captured in this manner can be tranquilized, released, translocated, or destroyed. Use baits as described previously to attract bears to foot snare sets.

The tools required for the pipe set are an Aldrich foot snare complete with the spring throw arm, a 9-inch (23-cm) long, 5-inch (13-cm) diameter piece of stove pipe, iron pin, hammer, and shovel. Cut a 1-inch (2.5-cm) slot, 6 1/2 inches (16.5 cm) long, down one side of the pipe. Place the pipe in a hole dug 9 inches (23 cm) deep into the ground. Cut a groove in the ground to accommodate the spring throw arm so that the pan will extend through the slot into the center of the pipe. The top of the pipe should be level with the ground surface. Anchor the pipe securely to the ground, where possible, by attaching it to spikes or a stake driven into the ground inside the can. Bears will try to pull the pipe out of the ground if it “gives.†The spring throw arm should be placed with the pan extending into the pipe slot 6 inches (15 cm) down from the top of the pipe. Pack soil around the pipe 1 inch (2.5 cm) from the top. Leave the pipe slot open and the spring uncovered. Loop the cable around the pipe, leaving 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) of slack. Place the cable over the hood on the spring throw arm, then spike the cable to the ground in back of the throw arm. The cable is spiked to keep it flush to the ground so that it will not unkink or spring up prematurely. Cover the cable loop with soil to the top of the pipe. Anchor the cable securely to a tree at least 8 inches (20 cm) in diameter. Cover the spring throw arm and pipe slot with grass and leaves. Place a few boughs and some brush around the set to direct the bear into the pipe. The slot in the pipe and the spring throw arm should be at the back of the set. The bear can approach the set from either side or the front. Melt bacon into the bottom of the pipe and drop a small piece in. The bacon should not lie on the pan. Other bait or scent, such as a fish-scented rag, may be used. Place a 15 to 20-pound (6.8- to 9-kg) rock over the top of the pipe. Melt bacon grease on the top of it or rub it on. The rock will serve to prevent humans, birds, nontarget wild animals, and livestock from being caught in the snare.

The bear will approach the set and proceed to lick the grease off the rock. It will then roll the rock from the top of the pipe and try to reach the bait with its mouth. When this fails, it will use a front foot, which will then be caught in the snare. The bear will try to reach the bait first with its mouth and may spring the set if the pan is not placed the required 6 inches (15 cm) below the top of the pipe. Pipe sets are more efficient, more economical, and safer than leghold traps.