In the early 1900s, black bears were classified as nuisance or pest species because of agricultural depredations. Times have changed and bear distributions and populations have diminished because of human activity. Many states, such as Colorado, Idaho, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin, manage the black bear as a big game animal. Most other states either consider black bears as not present or completely protect the species.In most western states, livestock owners and property owners may legally kill bears that are killing livestock, damaging property, or threatening human safety. Several states require a permit before removing a bear when the damage situation is not acute. In states where complete protection is required, the state wildlife agency or USDA-APHIS-ADC will usually offer prompt service when a problem occurs. The problem bear will be livetrapped and moved, killed, and/or compensation for damage offered. In a life-threatening situation, the bear can be shot, but proof of jeopardy may be required to avoid a citation for illegal killing.

Month: May 2007

Identification of Black Bear Damage

Damage caused by black bears is quite diverse, ranging from trampling sweet corn fields and tearing up turf to destroying beehives and even (rarely) killing humans. Black bears are noted for nuisance problems such as scavenging in garbage cans, breaking in and demolishing the interiors of cabins, and raiding camper’s campsites and food caches. Bears also become a nuisance when they forage in garbage dumps and landfills.Black bears are about the only animals, besides skunks, that molest beehives. Evidence of bear damage includes broken and scattered combs and hives showing claw and tooth marks. Hair, tracks, scats, and other sign may be found in the immediate area. A bear will usually use the same path to return every night until all of the brood, comb, and honey are eaten.

Field crops such as corn and oats are also damaged occasionally by hungry black bears. Large, localized areas of broken, smashed stalks show where bears have fed in cornfields. Bears eat the entire cob, whereas raccoons strip the ears from the stalks and chew the kernels from the ears. Black bears prefer corn in the milk stage.

Bears can cause extensive damage to trees, especially in second-growth forests, by feeding on the inner bark or by clawing off the bark to leave territorial markings. Black bears damage orchards by breaking down trees and branches in their attempts to reach fruit. They will often return to an orchard nightly once feeding starts. Due to the perennial nature of orchard damage, losses can be economically significant.

Few black bears learn to kill livestock, but the behavior, once developed, usually persists. The severity of black bear predation makes solving the problem very important to the individuals who suffer the losses. If bears are suspect, look for deep tooth marks (about 1/2 inch [1.3 cm] in diameter) on the neck directly behind the ears. On large animals, look for large claw marks (1/2 inch [1.3 cm] between individual marks) on the shoulders and sides.

Bear predation must be distinguished from coyote or dog attacks. Coyotes typically attack the throat region. Dogs chase their prey, often slashing the hind legs and mutilating the animal. Tooth marks on the back of the neck are not usually found on coyote and dog kills. Claw marks are less prominent on coyote or dog kills, if present at all.

Different types of livestock behave differently when attacked by bears. Sheep tend to bunch up when approached. Often three or more will be killed in a small area. Cattle have a tendency to scatter when a bear approaches. Kills usually consist of single animals. Hogs can evade bears in the open and are more often killed when confined. Horses are rarely killed by bears, but they do get clawed on the sides.

After an animal is killed, black bears will typically open the body cavity and remove the internal organs. The liver and other vital organs are eaten first, followed by the hindquarters. Udders of lactating females are also preferred. When a bear makes a kill, it usually returns to the site at dusk. Bears prefer to feed alone. If an animal is killed in the open, the bear may drag it into the woods or brush and cover the remains with leaves, grass, soil, and forest debris. The bear will periodically return to this cache site to feed on the decomposing carcass.

Black bears occasionally threaten human health and safety. Dr. Stephen Herrero documented 500 injuries to humans resulting from encounters with black bears from 1960 to 1980 (Herrero 1985). Of these, 90% were minor injuries (minor bites, scratches, and bruises). Only 23 fatalities due to black bear attacks were recorded from 1900 to 1980. These are remarkably low numbers, considering the geographic overlap of human and black bear populations. Ninety percent of all incidents were likely associated with habituated, food-conditioned bears.

Black Bear General Biology and Behavior

Black bears typically are nocturnal, although occasionally they are active during the day. In the South, black bears tend to be active year-round; but in northern areas, black bears undergo a period of semihibernation during winter. Bears spend this period of dormancy in dens, such as hollow logs, windfalls, brush piles, caves, and holes dug into the ground. Bears in northern areas may remain in their dens for 5 to 7 months, foregoing food, water, and elimination. Most cubs are born between late December and early February, while the female is still denning.

Black bears breed during the summer months, usually in late June or early July. Males travel extensively in search of receptive females. Both sexes are promiscuous. Fighting occurs between rival males as well as between males and unreceptive females. Dominant females may suppress the breeding activities of subordinate females. After mating, the fertilized egg does not implant immediately, but remains unattached in the uterus until fall. Females in good condition will usually produce 2 or 3 cubs that weigh 7 to 12 ounces (198 to 340 g) at birth.

After giving birth, the sow may continue her winter sleep while the cubs are awake and nursing. Lactating females do not come into estrus, so females generally breed only every other year. Parental care is solely the female’s responsibility. Males will kill and eat cubs if they have the opportunity. Cubs are weaned in late summer but usually remain close to the female throughout their first year. This social unit breaks up when the female comes into her next estrus. After the breeding season, the female and her yearlings may travel together for a few weeks. Black bears become sexually mature at approximately 3 1/2 years of age, but some females may not breed until their fourth year or later.

In North America, black bear densities range from 0.3 to 3.4 bears per square mile (0.1 to 1.3 bears/km2). Densities are highest in the Pacific Northwest because of the high diversity of habitats and long foraging season. The home range of black bears is dependent on the type and quality of the habitat and the sex and age of the bear. In mountainous regions, bears encounter a variety of habitats by moving up or down in elevation. Where the terrain is flatter, bears typically range more widely in search of food, water, cover, and space. Most adult females have well-defined home ranges that vary from 6 to 19 square miles (15 to 50 km2). Ranges of adult males are usually several times larger.

Black bears are powerful animals that have few natural enemies. Despite their strength and dominant position, they are remarkably tolerant of humans. Interactions between people and black bears are usually benign. When surprised or protecting cubs, a black bear will threaten the intruder by laying back its ears, uttering a series of huffs, chopping its jaws, and stamping its feet. This may be followed by a charge, but in most instances it is only a bluff, as the bear will advance only a few yards (m) before stopping. There are very few cases where a black bear has charged and attacked a human. Usually people are unaware that bears are even in the vicinity. Most bears will avoid people, except bears that have learned to associate food with people. Food conditioning occurs most often at garbage dumps, campgrounds, and sites where people regularly feed bears. Habituated, food-conditioned bears pose the greatest threat to humans (Herrero 1985, Kolenosky and Strathearn 1987).

Range, Habitat, and Food Habits of Black Bear

Range

Black bears historically ranged throughout most of North America except for the desert southwest and the treeless barrens of northern Canada. They still occupy much of their original range with the exception of the Great Plains, the midwestern states, and parts of the eastern and southern coastal states (Fig. 3). Black bear and grizzly/brown bear distributions overlap in the Rocky Mountains, Western Canada, and Alaska.

Habitat

Black bears frequent heavily forested areas, including large swamps and mountainous regions. Mixed hardwood forests interspersed with streams and swamps are typical habitats. Highest growth rates are achieved in eastern deciduous forests where there is an abundance and variety of foods. Black bears depend on forests for their seasonal and yearly requirements of food, water, cover, and space.

Food Habits

Black bears are omnivorous, foraging on a wide variety of plants and animals. Their diet is typically determined by the seasonal availability of food. Typical foods include grasses, berries, nuts, tubers, wood fiber, insects, small mammals, eggs, carrion, and garbage. Food shortages occur occasionally in northern bear ranges when summer and fall mast crops (berries and nuts) fail. During such years, bears become bolder and travel more widely in their search for food. Human encounters with bears are more frequent during such years, as are complaints of crop damage and livestock losses. Fig. 3. Range of the black bear in North America.

Identification of Black Bear

The black bear (Ursus americanus, Fig. 1) is the smallest and most widely distributed of the North American bears. Adults typically weigh 100 to 400 pounds (45 to 182 kg) and measure from 4 to 6 feet (120 to 180 cm) long. Some adult males attain weights of over 600 pounds (270 kg). They are massive and strongly built animals. Black bears east of the Mississippi are predominantly black, but in the Rocky Mountains and westward various shades of brown, cinnamon, and even blond are common. The head is moderately sized with a straight profile and tapering nose. The ears are relatively small, rounded, and erect. The tail is short (3 to 6 inches [8 to 15 cm]) and inconspicuous. Each foot has five curved claws about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long that are non-retractable. Bears walk with a shuffling gait, but can be quite agile and quick when necessary. For short distances, they can run up to 35 miles per hour (56 km/hr). They are quite adept at climbing trees and are good swimmers.

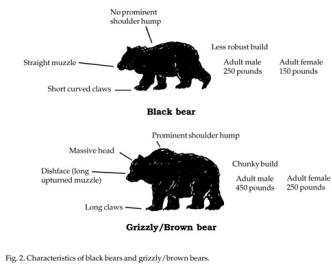

It is important to be able to distinguish between black bears and grizzly/ brown bears (Ursus arctos). The grizzly/brown bear is typically much larger than the black bear, ranging from 400 to 1,300 pounds (180 to 585 kg). Its guard hairs have whitish or silvery tips, giving it a frosted or “grizzly†appearance. Grizzly/brown bears have a pronounced hump over the shoulder; a shortened, often dished face; relatively small ears; and long claws (Fig. 2).

Controlling Feral Cats

Identification

The cat has been the most resistant to change of all the animals that humans have domesticated. All members of the cat family, wild or domesticated, have a broad, stubby skull, similar facial characteristics, lithe, stealthy movements, retractable claws (except the cheetah), and nocturnal habits.

Feral cats (Fig. 1) are house cats living in the wild. They are small in stature, weighing from 3 to 8 pounds (1.4 to 3.6 kg), standing 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30.5 cm) high at the shoulder, and 14 to 24 inches (35.5 to 61 cm) long. The tail adds another 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30.5 cm) to their length. Colors range from black to white to orange, and an amazing variety of combinations in between. Other hair characteristics also vary greatly.

Range

Cats are found in commensal relationships wherever people are found. In some urban and suburban areas, cat populations equal human populations. In many suburban and eastern rural areas, feral house cats are the most abundant predators.

Habitat

Feral cats prefer areas in and around human habitation. They use abandoned buildings, barns, haystacks, post piles, junked cars, brush piles, weedy areas, culverts, and other places that provide cover and protection.

Food Habits

Feral cats are opportunistic predators and scavengers that feed on rodents, rabbits, shrews, moles, birds, insects, reptiles, amphibians, fish, carrion, garbage, vegetation, and leftover pet food.

General Biology, Reproduction, and Behavior

Feral cats produce 2 to 10 kittens during any month of the year. An adult female may produce 3 litters per year where food and habitat are sufficient. Cats may be active during the day but typically are more active during twilight or night. House cats live up to 27 years. Feral cats, however, probably average only 3 to 5 years. They are territorial and move within a home range of roughly 1.5 square miles (4 km2). After several generations, feral cats can be considered to be totally wild in habits and temperament.

Damage

Feral cats feed extensively on songbirds, game birds, mice and other rodents, rabbits, and other wildlife. In doing so, they lower the carrying capacity of an area for native predators such as foxes, raccoons, coyotes, bobcats, weasels, and other animals that compete for the same food base.

Where documented, their impact on wildlife populations in suburban and rural areas—directly by predation and indirectly by competition for food— appears enormous. A study under way at the University of Wisconsin (Coleman and Temple 1989) may provide some indication of the extent of their impact in the United States as compared to that in the United Kingdom, where Britain’s five million house cats may take an annual toll of some 70 million animals and birds (Churcher and Lawton 1987). Feral cats occasionally kill poultry and injure house cats.

Feral cats serve as a reservoir for human and wildlife diseases, including cat scratch fever, distemper, histoplasmosis, leptospirosis, mumps, plague, rabies, ringworm, salmonellosis, toxoplasmosis, tularemia, and various endo- and ectoparasites.

Legal Status

Cats are considered personal property if ownership can be established through collars, registration tags, tattoos, brands, or legal description and proof of ownership. Cats without identification are considered feral and are rarely protected under state law. They become the property of the landowner upon whose land they exist. Municipal and county animal control agencies, humane animal shelters, and various other public and private “pet†management agencies exist because of feral or unwanted house cats and dogs. These agencies destroy millions of stray cats annually.

State, county, and municipal laws related to cats vary. Before lethal control is undertaken, consult local laws. If live capture is desired, consult the local animal control agency for instructions on disposal of cats.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Exclusion

Exclusion by fencing, repairing windows, doors, and plugging holes in buildings is often a practical way of eliminating cat predation and nuisance. Provide overhead fencing to keep cats out of bird or poultry pens. Wire mesh with openings smaller than 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) should offer adequate protection.

Cultural Methods

Cat numbers can be reduced by eliminating their habitat. Old buildings should be sealed and holes under foundations plugged. Remove brush and piles of debris, bale piles, old machinery, and junked cars. Mow vegetation in the vicinity of buildings. Elimination of small rodents and other foodstuffs will reduce feral cat numbers.

Repellents

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has registered the following chemicals individually and in combination for repelling house cats: anise oil, methyl nonyl ketone, Ro-pel, and Thymol. There is little objective evidence, however, of these chemicals’ effectiveness. Some labels carry the instructions that when used indoors, “disciplinary action†must reinforce the repellent effect. Some repellents carry warnings about fabric damage and possible phytotoxicity. When used outdoors, repellents must be reapplied frequently. Outdoor repellents can be used around flower boxes, furniture, bushes, trees, and other areas where cats are not welcomed. Pet stores and garden supply shops carry, or can order, such repellents. The repellents are often irritating and repulsive to humans as well as cats.

Frightening

Dogs that show aggression to cats provide an effective deterrent when placed in fenced yards and buildings where cats are not welcome.

Toxicants

No toxicants are registered for control of feral cats.

Fumigants

No fumigants are registered for control of feral house cats. Live-trapped cats or cats in holes or culverts can be euthanized with carbon dioxide gas or pulverized dry ice (carbon dioxide) at roughly 1/2 pound per cubic yard (0.3 kg/m3) of space.

Trapping

Urban and Suburban Wildlife Populations

As the human population increases and we urbanize more rural areas, we change the character and functionality of the land, air, and water. These changes greatly impact local habitats and native wildlife. As these habitats are impacted, a corresponding shift in wildlife populations impacts both us and them.Nuisance wildlife issues – As we move out into raw land, radical changes occur to sources of food, water, and shelter for endemic wildlife that live in the area. Some animals respond very well to the changes urbanization brings. However, in many cases, it is these animals that seem “fun” and “neat” at first, but then become a realized nuisance.